Investor Insight Newsletter: science-based stewardship - October 2025

This is an excerpt from our October newsletter. Subscribe to receive our latest research, insights and updates directly to your inbox.

We’ve noticed recently an uptick in conversations within the investment community about adaptation.

This is not surprising. With extreme weather events continuing to unfold across the globe – the ecological and economic damage caused by a marine heatwave in South Australia just the latest – it is logical that investors are starting to more actively contemplate the vulnerability of their portfolios to climate change.

“To date, much investor action on climate-related risk has focused on climate mitigation: reducing carbon emissions with the aim of limiting the long-term rise in global temperatures. However, research shows these efforts will not be enough to limit significant physical and economic damage without adaptive interventions.”

Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), June 2025“Climate adaptation is an inevitable need and investment opportunity”.

Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC)

While we agree that adaptation is relevant to the investment community, we would be concerned if this renewed interest comes at the expense of intensifying efforts towards mitigation.

Adaptation has hard limits – some of which may already have been breached.[1] Low-lying coastal settlements cannot be protected indefinitely from rising seas; the human body cannot adapt to certain levels of extreme heat; and the collapse of ecosystems such as coral reefs — a vital food source for billions — cannot be reversed.

Insurers are warning that we are approaching temperatures which will result in impacts they cannot insure against, where adaptation become economically unviable. When the economic value of entire regions begins to erode, markets will re-price “rapidly and brutally”.[2]

Based on current policies, the average projected warming is 2.7°C. On this trajectory, no amount of adaptation investment or technological ingenuity will prevent the arrival of compounding extremes. Global tipping points relating to crop failure, for example, will have impacts not just on food systems, but on political and social stability.[3]

What this means is that without urgent and sustained mitigation – that is, rapidly reducing fossil fuel emissions – adaptation alone is economically unsustainable and ultimately futile.

Investors who are considering the adaptation opportunities being presented at the moment, but who are not focused on tackling emissions head-on, risk their adaptation efforts becoming performative, or worse, maladaptive. If adaptation is chosen over mitigation, the danger is it becomes an instrument of delay.

Building true climate resilience – in portfolios, markets and economies – requires mitigation first and foremost. This means engaging with companies and governments to drive down fossil fuel emissions at speed and scale.

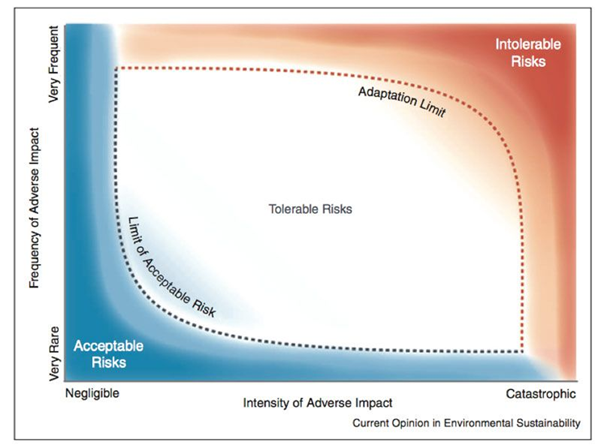

Figure 1 shows how beyond a point of adverse impact intensity and frequency, no new adaptation options are available. It is also the point at which it becomes unviable to implement adaptation optionality. Below that sits a window of tolerable risks for which adaptation can viably occur.

Question of the Quarter

Dr Sophie Lewis, ACCR Chief Scientist - Engagement

What do we need to know about Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment?

Nearly three years, 300 pages and hundreds of experts in the making, the National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA) is a systematic examination of Australia’s climate risks. It explores 10 key climatic hazards across 11 Australian regions through eight systems, ranging from the economy to water security. Australia’s vulnerability to climate change in 2050 and 2090, at +1.5, +2 and +3 degrees of global warming, is examined.

The assessment demonstrates that we must prepare for the impacts of committed climate change and we must act fast to avoid the impacts that will come with warming above +1.5°C.

What climate impacts do we need to prepare for?

The impact of climate change is already being felt in every part of Australia through frequent, severe and complex extreme weather events that have financial impacts on individuals, households and businesses. Climate change is bringing high risks to defence and national security, and to food production capacity in some regions.

Because the climate system responds slowly to changes in atmospheric CO2? - even after greenhouse gas emissions peak the planet will continue to warm for decades - we are already committed to the impacts of this ‘baked in’ warming.

The NCRA tells us what we need to prepare for under +1.5°C of warming:

- All 11 regions should expect extreme weather events, sea level rise and water security challenges.

- Sydney should prepare for a doubling of heat-related mortality, and plan for impacts on the economy, particularly through labour productivity.

- Nearly 600,000 coastal Australians should prepare for a ‘high’ or ‘very high risk’ of coastal erosion or inundation from sea level rise.

Infrastructure is vulnerable too. While critical infrastructure is engineered for significant climate variability, climate change will push some infrastructure beyond design envelopes. Transport and supply chain infrastructure, energy infrastructure and water security infrastructure are at ‘high risk’. At +1.5°C warming, almost one-fifth of residential buildings in the Northern Territory will be in ‘high-risk’ and ‘very high-risk' areas. In Queensland alone, 178,000 residential buildings will be in ‘very high-risk' areas.

What happens if we reach higher levels of warming?

The NCRA outlines distinct pathways for Australia’s future that are differentiated by global warming levels. While the challenge of adapting to +1.5°C of global warming is immense, the NCRA demonstrates that warming of +2.0°C and +3.0°C must be avoided. These climate impacts are beyond the capacity of systems to adapt and cope.

At higher levels of warming:

- Extreme impacts are expected across all regions. Up to 2.7 million additional days of work are projected to be lost each year in agriculture, construction, manufacturing and mining.

- 20.5 million people in three major cities could simultaneously experience heatwaves over 44°C.

- Over three million people could be living in areas that will experience sea level rise and coastal flooding risks.

The risks are likely underestimated: at +2.0°C or +3.0°C of warming, the past no longer gives us insights into future risk. Changes in the timing, duration, intensity and spatial patterns of hazards are likely, with many events occurring more frequently, in combination or affecting new locations. More frequent and more intense extreme events will affect all aspects of live, damage property, infrastructure and energy sources, and degrade water quality. Australians in high climate risk areas will be displaced, and the disruption of relocations will flow through all parts of our lives and ripple across sectors, services and structures.

Climate impacts are systemic, less certain and beyond adaptive measures.

What didn’t we get from this review?

- There’s a lot we still don’t know. Our understanding of some climate hazards and systems is stronger than others. Science provides greater confidence in changes in temperature, but we need to increase our understanding of riverine flooding, tropical cyclones, storms and droughts.

- Australia is connected to the rest of the world. The NCRA is domestically focused. Significant risks will be driven by climate change-related impacts outside of Australia’s borders, including supply chain disruptions. Climate-related financial system shocks or volatility in international markets will have ripple effects on the Australian economy.

- Tipping points and other abrupt changes. The NCRA does not explore tipping points and other abrupt changes in the climate system in detail, although several climate tipping points may be triggered this century even with 2°C of warming. Without full consideration of extremes in the climate system, assessments of climate risks are limited.

What’s the key takeaway from the NCRA?

The NCRA is more than just a wake-up call for investors. It is a loud and clear siren warning us of the escalating costs of climate change with every increment of future warming. Mitigation is just as important as adaptation and cannot be neglected.

Science-based stewardship

Dimitri Lafleur, ACCR Chief Scientist - Insights

A few months ago, I attended the Global Tipping Point Conference at the University of Exeter in the UK. It was a powerful display of research on the dire state of deteriorating climate systems, and it also showed how quickly human systems can turn towards a more sustainable direction.

While there was lots to digest, here are my two key takeaways from the conference.

- Erosion of the resilience of Earth systems may lead to tipping points coming earlier than originally thought: The resilience of Earth systems like the Amazon, tropical coral reefs and the polar icesheets are being severely eroded by various and compounding stressors. Scientific analysis of this erosion shows these systems reaching tipping points much earlier than analysis that only looks at temperature.

For example, while temperature modelling has suggested that the Amazon reaches a tipping point at ~3.5°C (range: 2-6°C)[4], the compounding effects of deforestation, increasing droughts, a longer dry season, increased tree mortality and changes in atmospheric moisture, may put a tipping point between 1 and 2°C. It is now widely accepted that the Amazon is already a carbon source, rather than a carbon sink.[5]

- Positive, unstoppable change is also happening: While I don’t want to create confusion about the phrase “tipping points” - in climate science we use this to describe irreversible changes to Earth systems - I do want to highlight what many at the conference called “positive tipping points”. For example, in various countries the rate of EV market share gain is now so large that it has likely passed its tipping point.[6] This is an important signal for investors and policymakers alike, who are now more incentivised to advocate for investment into specific future-proof technologies.

The few investors present at the conference were keen to understand what the impact could be of tipping points (the planetary destabilising type) materialising. This interest appeared to be primarily from the position of safeguarding current investments by wanting to understand what adaptation would be required. However, the view from the scientific community is that the most important and urgent consideration is to take actions that prevent the tipping point in the first place.

https://10insightsclimate.science/year-2022/questioning-the-myth-of-endless-adaptation/#:~:text=Soft limits can be overcome,and societies'%20response%20to%20them. ↩︎

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/climate-risk-insurance-future-capitalism-günther-thallinger-smw5f/ ↩︎

https://report-2023.global-tipping-points.org/section2/2-tipping-point-impacts/2-2-assessing-impacts-of-earth-system-tipping-points-on-human-societies/2-2-6-sector-based-impacts-assessment-of-climate-system-tipping-points/2-2-6-2-food-security/#:~:text=2.2.-,6.2 Food security,disturbance (Gaupp%2C 2020). ↩︎

Armstrong McKay, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7950 ↩︎

Gatti, et al., 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06390-0 ↩︎

Preprint: Mercure, J.-F. et al., 2024, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3979270/v1 ↩︎